Activision Seeks Out Army National Guard Combat Vet

On a white, snow-packed mountainside in eastern France not long after New Year’s Day 1945, PVT Harold Angle of the 28th Infantry Division, Pennsylvania Army National Guard, found himself in the mother of all shootouts.

He had just joined his unit as a replacement Soldier for I Company in the 112th Regiment. Now he was deployed as a scout on the forward left flank of his platoon as they climbed the Vosges Mountains. American divisions, including Pennsylvania’s 28th Infantry Division, were pushing deeper into France and threatening the Nazi presence occupying the European country.

U.S. troops were moving steadily. Each march eastward was a step closer to ending forever the malevolent force that was Hitler’s Third Reich. But until then, the might of the German army would fight with everything it had to halt the U.S. advance.

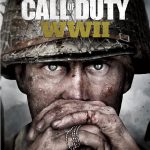

Now a retired civilian, Angle was recently asked to describe these dramatic events that took place 72 years earlier. Members of the video gaming company Activision listened intently last October as the 94-year-old veteran told them his story. They were consulting with him and other vets to make sure their soon-to-be-released video game – Call of Duty: WWII® – was as authentic as possible.

Angle’s days in combat so long ago were brief, but chilling. Reflecting back, he said that even though he didn’t see a lot of combat before the war ended in 1945, what he did see was enough to last a lifetime.

The Guard Soldier took the fight to the Germans that January day when he and his platoon had attempted to assault a German machine gun position. But their sergeant tripped a wire hidden under the snow. Light from flares illuminated the mountainside like sunshine, and the Nazi troops began pouring machine gun fire onto the Americans’ position. Fortunately, protected by a depression in the earth, the Soldiers were able to avoid the onslaught of bullets but were pinned down until dawn.

The Soldiers didn’t give up on their mission. Instead, they decided to go up the mountain from the backside.

It was during this latter climb when PVT Angle spotted a group of soldiers across a clearing. Were they friend or foe? One of the advancing men had not pulled his white helmet-camo completely down, revealing the telltale signs of German headgear. PVT Angle immediately signaled his fellow Soldiers to hit the ground.

Then the shooting began.

Bullets rained between the American and German positions. PVT Angle aimed his M1 Garand rifle from a prone position and began firing on the Nazis. Just months before, the small-town boy from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, had been helping his Dad with the family business, selling eggs and poultry to the residents of the Keystone State. Now he was a Soldier in the Pennsylvania Army National Guard fighting to save the world.

“During the exchange of fire, one of the bullets came in,” Angle recalled. “I was in the prone position lying in the snow. One of the bullets hit the brim of my helmet. That bullet went past my ear, and tore the wool-knit cap I was wearing all to shreds. It never touched my ear, but the bullet went to my right shoulder. I didn’t know how bad I was hurt. When that bullet hit my shoulder, it stunned me so bad that I literally blacked out.”

When PVT Angle came to, he resumed returning fire on the Germans with the rest of his platoon. Then the potato masher came at him. The potato masher was a German-designed hand grenade that got the name because it somewhat resembled the kitchen utensil.

As he told the memory of the weapon flying toward him, you could still hear the alarm in Angle’s voice.

“It landed only two to three feet from where I was laying,” Angle recalled. “I saw it coming. I put my face down into the snow, covered my head as much as I could with my arms, and I said a quick prayer. I said ‘God, protect me.’ That grenade landed two or three feet in front of me and it never exploded. It was a dud.”

Later, after the skirmish was over and the Germans had retreated back into heavier cover, PVT Angle went toward the rear of his unit to have his shoulder checked out. The medic told him to take off his coat and shirt. When he complied, a spent bullet fell to the ground.

The German slug had lost its momentum before reaching PVT Angle’s shoulder. He was not awarded a Purple Heart because he only had a bruise. He did keep the bullet though as a souvenir of his good fortune. He sent it home from Paris in a jewelry box to his mother, who had given him a steel-covered Bible to keep over his heart. Angle admitted that she was probably “pretty disturbed” upon receiving it from her son.

He still has the bullet today, and proudly shows it off when asked about his time in the war. Angle has lived in his home in Chambersburg since not long after leaving the Service in 1946. Once a small-town boy, he is now a small-town elder – one who is increasingly called upon for media interviews and memorial ceremonies as his peers pass away.

Angle is part of the Greatest Generation – the fading few who once made the world safe and championed democracy. They battled and defeated a rising evil that almost took over the world between 1941 and 1945. They were simply citizens, doing what they had to do. Many of them were Army National Guard Soldiers like Angle.

Call of Duty: WWII® is now a hit video game from Activision and Sledgehammer Games. The game allows players to perform some of their own WWII heroics, and the game makers wanted the option of heroics offered in the game to be as realistic as possible.

Activision contacted the Greatest Generation Foundation and brought Angle and several other World War II combat vets to Hollywood last October. It was a first-class affair – first-class airfare, five-star hotel, the works – all so they could learn more about the reality of World War II combat.

“The reason why Activision wanted to do this – they said a lot of the school districts in the United States do not teach WWII history anymore,” Angle said. “They felt that if they tried to incorporate the stories of actual veterans that were in combat during WWII, it would give them better insight as to what WWII was really like. In that respect, I’m glad I was able to do what I did. Hopefully, young people won’t have to do what we had to.”

The old adage “experience is the best teacher” takes on a new meaning when some argue that using gaming for education, including Army National Guard history, is beneficial to players. The Army already uses gaming in some aspects of Soldier combat training; why not also use it to teach Army history?

“I would encourage it,” said MAJ Darrin Haas, historian for the Tennessee Army National Guard. “I think not only are you entertaining, but you’re also teaching. You can never learn enough about your past, your heritage and where you come from.”

MAJ Haas went on to talk a little about the Army National Guard’s contribution to World War II.

“You’re talking about the 29th Division coming in at Omaha Beach,” he said. “You’re talking about the 30th Division – the workhorse of the Western Front – you never hear about those guys. I don’t think they get as much attention as they deserve. I think that’s a shame.”

The 28th and 45th Army National Guard Infantry Divisions also served in the European Theater of Operations during the war.

Those in the gaming industry are optimistic about teaching history through gaming. Perhaps that’s because it’s a popular medium for young people and it can actually put a player inside different historic (and action-packed) scenarios.

Angle is still looking forward to getting an up-close view of 1945 Europe through the lens of Activision’s final product. He has yet to play Call of Duty: WWII®, as he does not have Internet at his home, but said he would like to see it.

While the Pennsylvania Army National Guard veteran is humble about his contribution to the Allied victory, he is hopeful about what his contribution to Call of Duty: WWII® might bring to others.

“Don’t call me a hero,” he emphasized. “I’m just a survivor – a survivor of what was thrown at me. I think the game will give the young people somewhat of an education of what war is like, what it can be and the devastation that is involved.”

By Staff Writer Matthew Liptak