46th Military Police Command Helps Pioneer Groundbreaking Training Format

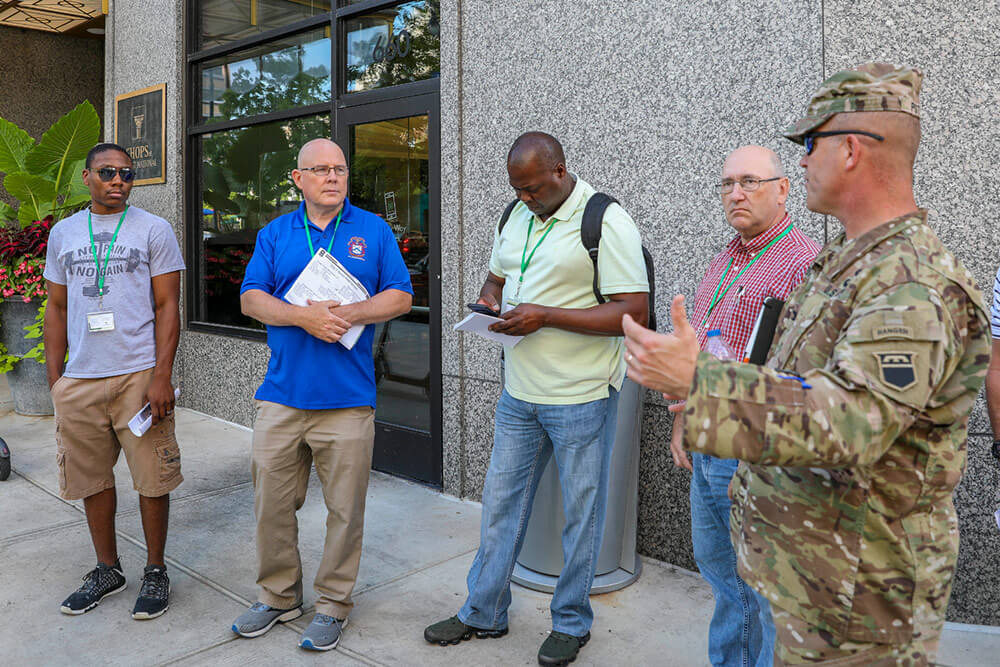

The wave of the future for National Guard disaster recovery training is cresting today. As U.S. troops continue to battle our Nation’s enemies in urban locations like Fallujah, Iraq, mastering what it takes to successfully navigate battlefields in densely populated environments has never been more vital. A new training system is directly responding to this need. In this new-age format, role players are out and real officials are in. This new format was demonstrated last August when the Michigan Army National Guard held its dense urban terrain (DUT) exercise in downtown Detroit, Michigan, showcasing the execution of disaster recovery planning within a real-world urban setting, using real-world local and State officials as participants.

This first tabletop exercise was the initial phase of what is planned to be a three-year exercise effort. The Michigan Army National Guard’s 46th Military Police Command, one of three Army-wide command elements responsible for responding to chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) attacks on the homeland, is leading the DUT initiative. In responding to a real attack, the 46th would be tasked with coordinating with civilian agencies to protect lives and initiate recovery efforts.

“There are certain artificialities – role playing – that occur when you go to training installations,” said MG Michael A. Stone. MG Stone is commanding general of the 46th Military Police Command as well as assistant adjutant general of the Michigan National Guard and deputy director of Michigan’s Department of Military and Veterans Affairs.

“Where this is different and unique is in the sense that we are working with the actual people in Detroit that would actually be responding. It translates better. We are not role-playing, where you are walking up to a building and pretending someone is the mayor. We actually sat down with the mayor of Detroit. It presents the problem differently when you have to interact with the real players.”

MG Stone cited three improvement factors involved with this new modality of training in comparison to traditional training with role players at fixed training installations.

The first notable improvement was that civilian organizations and first responders were included in the prior planning leading up to the exercise. Together, the civilian teams and Michigan Guard teams negotiated the training scenario to fit existing emergency response plans within the city, MG Stone said.

“Often the military will come in and say, ‘Hey, we’re doing an exercise. Do you want to play with us in this situation?’”

In contrast, this new process interweaves the civilian agencies into the exercise development so the resulting training builds on the actual requirements of civilian first responders, while also remaining aligned with National Guard requirements.

A second improvement noted by MG Stone is the time given for civil agencies to back-brief the Army National Guard planners on the local agency capabilities.

“We have this national-response framework that we work within when an incident happens, but the locals are the ones who know what their capabilities are. Many times, our senior leaders and our Soldiers in uniform are not briefed on what those capabilities are,” MG Stone noted.

The third improvement was the introduction of academic experts into the overview and analysis of the exercise.

“We brought a lot of brainpower,” MG Stone noted. That brainpower included experts and Ph.D.s from Michigan University, Michigan State University and U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, all of whom “added a lot to the intellectual capacity of the learning experience,” said MG Stone.

Twelve Army National Guard units from seven States – Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina and Tennessee – and units from both active duty and the Reserves participated in the 2018 DUT exercise. Also participating, and vital to the overall success of the exercise, were 28 government and civilian agencies and organizations, including several Canadian agencies. (As Detroit shares a border with Windsor, Ontario, Canada, citizens in the southern regions of Ontario could be affected by a biological or chemical attack detonated in the Detroit area.)

SFC Joseph Paul Fry was one of 200 participants at Michigan’s DUT and one of the developers of the training scenarios. As a first-time scenario writer, SFC Fry said he really enjoyed the undertaking, though a hefty amount of preparation and discovery went into the process. That preparation included six meetings with local partners in Detroit where SFC Fry and other team members reviewed each scenario, assessed local capabilities and discussed the local government’s current readiness factor for an actual incident.

“Something that surprised me at the exercise was the willingness of our civilian partners to roll up their sleeves and get in right next to a Soldier and figuring out the problems,” SFC Fry said.

He went on to note that he was impressed by the synergy between the first responders and the Guard Soldiers, which enabled the many organizations to come together and build momentum in a very short period of time.

MG Stone noted some unexpected outcomes on his end as well.

“There were a few surprises [in regard to] capabilities from both the city and the State of Michigan for emergency response to a chemical attack,” he said. “For instance, the amount of atropine that public health [agencies] could deliver to citizens was well beyond what I thought the limits would be.”

According to MG Stone, the response from the community hospital and the coordinated response from the local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) agency were also revealing. Though he had been briefed on local CDC capabilities in the past, MG Stone said the organization had continued work toward resiliency, and he was pleasantly surprised by the progress made.

MG Stone also noted surprise when learning how often the Detroit first responders actually train on disaster response efforts. While the training is often on a smaller scale, the general acknowledged, “Their exercise frequency was more robust than I expected.”

In fact, the collaboration with the civilian groups was so well-aligned that the main training scenario was developed based on a suggestion given by one of the civilian agencies – the Detroit Fire Department.

“The specific scenario was a complex attack from the Universal Opposition Collective,” SFC Fry said. “That’s the [fictional] group we created. It was set to be a complex attack, including a biological assault, a chemical assault and a cyber assault.”

“The exercise itself began with the attacks,” said COL Chris A. McKinney with the 46th Command and Control CBRN Response Enterprise-B, Michigan Army National Guard. “The attacks were a combination of a cyberattack on the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System, a biological attack on an all-day, widely attended 4th of July concert, and an explosive attack on four railcars [carrying] a toxic chemical. We broke out into work groups to address the different scenarios by emergency support function.”

Those involved in the response conducted terrain walks that took them through the areas of the city directly affected by the hypothetical man-made disaster. Those areas included the riverfront of the Detroit River, the roofs of the Renaissance Center – a group of seven interconnected skyscrapers in Downtown Detroit – and the steam tunnels running under the city.

COL McKinney said climbing a ladder down into the city steam tunnels felt like entering a “full body hair dryer set on high-hot.”

MG Stone described the layout of the tunnel system. “[In some places,] they are 7 to 8 feet tall,” he explained. “In other places, they are like small caverns. They run all throughout the city. [The city workers took the temperatures] down for us to about 110 to 120 degrees. It’s made of about four layers of brick that were laid in the 1920s. People don’t realize how much subterranean infrastructure there is.”

According to MG Stone, the planners initially discussed scenarios with workers being trapped underground. The possibility of using the tunnel system to evacuate people out of a hot zone and to a safer place for decontamination was also considered. These considerations stemmed from training in a real-world environment. Such options would not have been possible in the mock environments available at most traditional training centers.

MG Stone commented that in exercises held at traditional facilities, certain levels of friction are often removed from the training scenarios to allow participants to reach objectives within expected timeframes. In this new modality, designers have begun to understand that the friction was, in fact, the crux of the training. Immersing Soldiers in a real-world disaster environment offers both a broader range of variables to confront and requires a more detailed understanding of participating organizations’ capabilities.

This shift may be considered groundbreaking by some, but in actuality it has been moving towards development for some time.

“It started with a relationship with COL [ret.] Kevin Felix,” MG Stone revealed. “When he was still on active duty, he wrote white papers on megacities and the complexities of the future for the Department of the Army. I’ve pretty much picked up the pieces where other people had the idea, and I think COL McKinney and I were the two that figured out how to operationalize it.”

The future of this new DUT training template looks bright. Tentatively scheduled is a command post exercise in the spring of 2019, which will follow up on the August 2018 event with more complicated simulated mission parameters and a fuller exercise of the 46th Military Police Command’s capabilities and personnel. Then, during a mid-2020 field training, a culminating event is expected for the DUT that would include a full complement of the command’s mission personnel, with more complex and elaborate mission-enhancing activities.

by Staff Writer Matthew Liptak