A Guard Soldier’s Best Friend

Across the United States in the late spring of 1917, millions of Americans were preparing to enter the “war to end all wars” that had been raging across Europe for years. The United States declared war on Germany in April, resulting in thousands of Army National Guard Soldiers being mobilized in their home states to train and ready themselves for combat in France.

In Connecticut, hundreds of National Guard Soldiers from the 1st and 2nd Connecticut Infantry headquartered in Hartford and New Haven attended training camps, with a large contingent at Camp Yale – a mobilization camp on the Yale University campus in New Haven.

As the Soldiers trained, they weren’t the only ones interested in preparing for war. One day, while the men were drilling, a stray dog wandered onto the Yale campus and starting watching the men. He began hanging around the Soldiers, and they played with him during breaks and in their time off. The mutt, a mixed-breed believed to be part pit bull terrier or Boston terrier, followed the Soldiers around the camp and even participated in some of their drills.

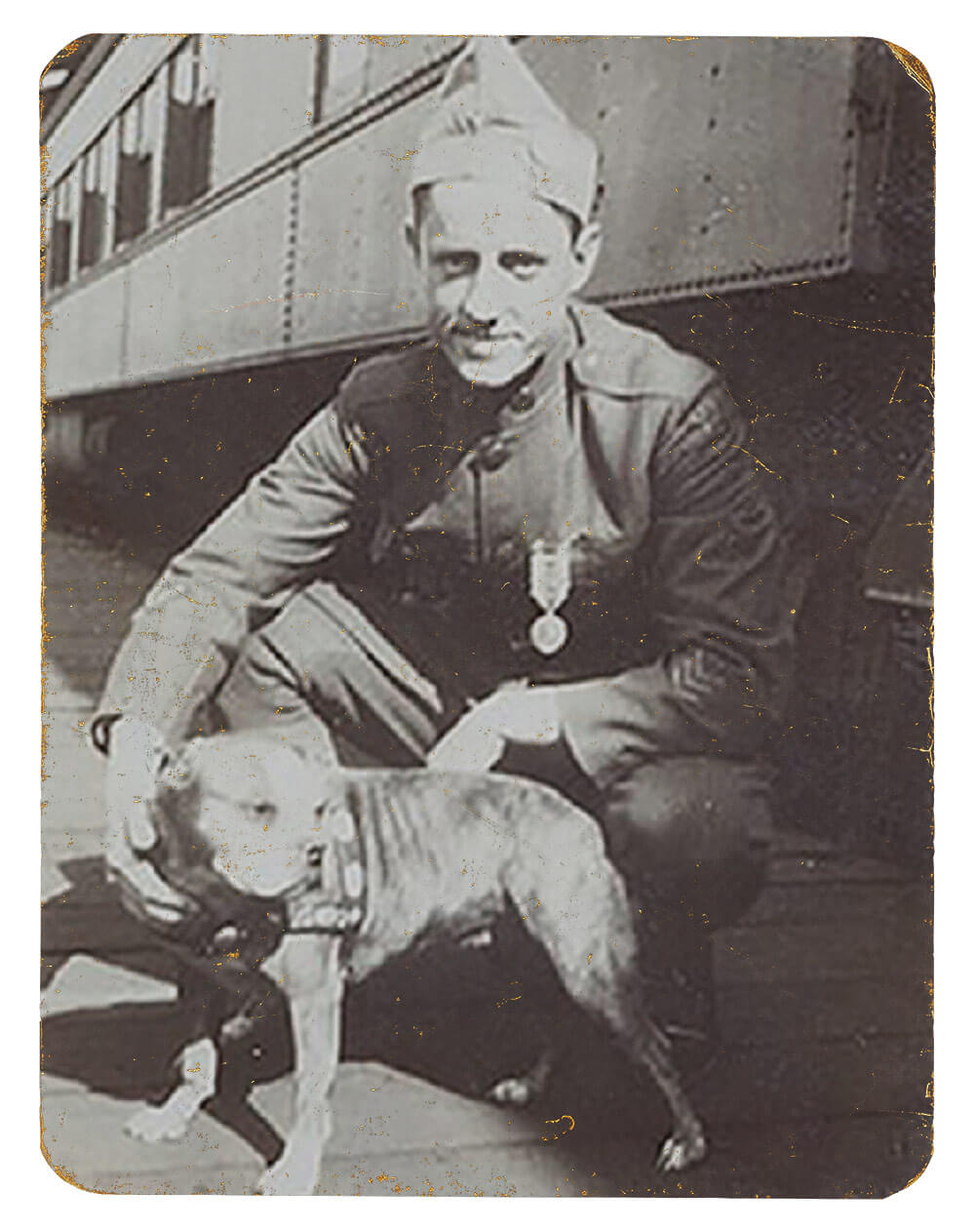

The dog was a great morale boost for the Soldiers during their long days of training and time away from home, and they made him an unofficial mascot. One of the Soldiers, J. Robert Conroy, a 25-year-old private from New Britain, Connecticut, forged the closest bond with the dog and named him “Stubby” because of his short tail. He also taught Stubby how to salute and perform some of the unit’s marching commands.

After a few months, the Connecticut units were merged into the 102nd Infantry Regiment under the 26th “Yankee” Division. Eventually, they were ordered to sail for France, but the Soldiers did not want to leave their mascot behind. So PVT Conroy smuggled Stubby onto the train heading to the port, and then onto the troop ship, hiding him under an overcoat to get past the ship’s guards.

Once on board, he kept him hidden in the ship’s coal hold as they sailed across the Atlantic. The ruse didn’t last long, as PVT Conroy’s commander soon discovered Stubby. As the officer decided whether to send the dog home, Stubby saluted him, just like he was trained to do back at Camp Yale. Because of this, the officer decided to let Stubby stay on board as long as he didn’t cause any problems.

No longer in hiding and free to roam the ship, Stubby became very popular with the crew. One of the ship’s machinists made Stubby his own set of metal “dog tags.” When the troops finally disembarked in the port of Saint-Nazaire on France’s western coast after crossing the Atlantic, Stubby disembarked as the unit mascot.

Eventually, COL John Parker, the regimental commander, gave special orders that Stubby was to remain with the 26th Division throughout the war. One Soldier said Stubby “was the only member of his regiment that could talk back to [COL Parker] and get away with it.”

On Feb. 5, 1918, the 102nd entered the trenches at Chemin des Dames, north of Soissons, where Soldiers were under constant fire for over a month. Stubby was right alongside them. Unfortunately, shortly after entering the trenches, he was injured by mustard gas after an enemy attack. He was removed from the trenches for a short period to recover, then returned to the front line with a specially designed gas mask for protection.

After his injury, Stubby learned to identify the presence of gas and started warning Soldiers when he sensed the deadly chemicals were present. During one attack, he ran through the trenches warning sleeping Soldiers of the danger, barking and nipping at them, saving hundreds.

Stubby also learned to perform other combat tasks to help the Soldiers of the 102nd. He assisted medics in locating wounded men on the battlefield, he could hear the whine of incoming shells before humans and warn them of the threat, and he was there to improve morale and remind everyone of home.

In April 1918, Stubby was wounded. During a German raid into the allied trenches, he was on top of a trench helping to repulse the intruders. As the Germans retreated, they threw hand grenades to cover their escape. One of the grenades went off and some of the shrapnel hit Stubby in the foreleg and chest. After the raid, he was evacuated from the trenches for medical treatment, where he recovered from his wounds while also lifting the morale of the other injured men. Once he recovered, Stubby returned to the trenches.

Stubby didn’t just endear himself to Soldiers. After the 102nd retook Château-Thierry from the Germans, many of the women in town wanted to repay the Soldiers and Stubby for their help. They made him a coat to keep him warm and on which to pin his medals.

Toward the end of the war, Stubby made a major contribution in the capture of a German spy. After the spy infiltrated an allied foxhole, Stubby discovered him, gave chase and attacked the German, biting him on the rear and holding him until American troops could capture him.

Because of this action, Stubby was recommended for a promotion to sergeant, and he became the first dog in the American military to be awarded the rank. (Whether Stubby was “officially” promoted has been questioned.) The German prisoner was also wearing an Iron Cross, which the Americans took from him and pinned onto Stubby’s coat.

Stubby fought alongside the Guard Soldiers of the 102nd Infantry Regiment for 10 months, participating in four offensives: Aisne-Marne, Champagne-Marne, St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne. He would participate in 17 battles, and the unit awarded him multiple medals for bravery and even a Purple Heart.

For the return trip to the United States, PVT Conroy still had to smuggle Stubby back aboard the troop ship. Because Stubby was now well known after being written about in many of the newspapers back home, it was a much easier voyage, with many of the officers turning a blind eye to the stowaway.

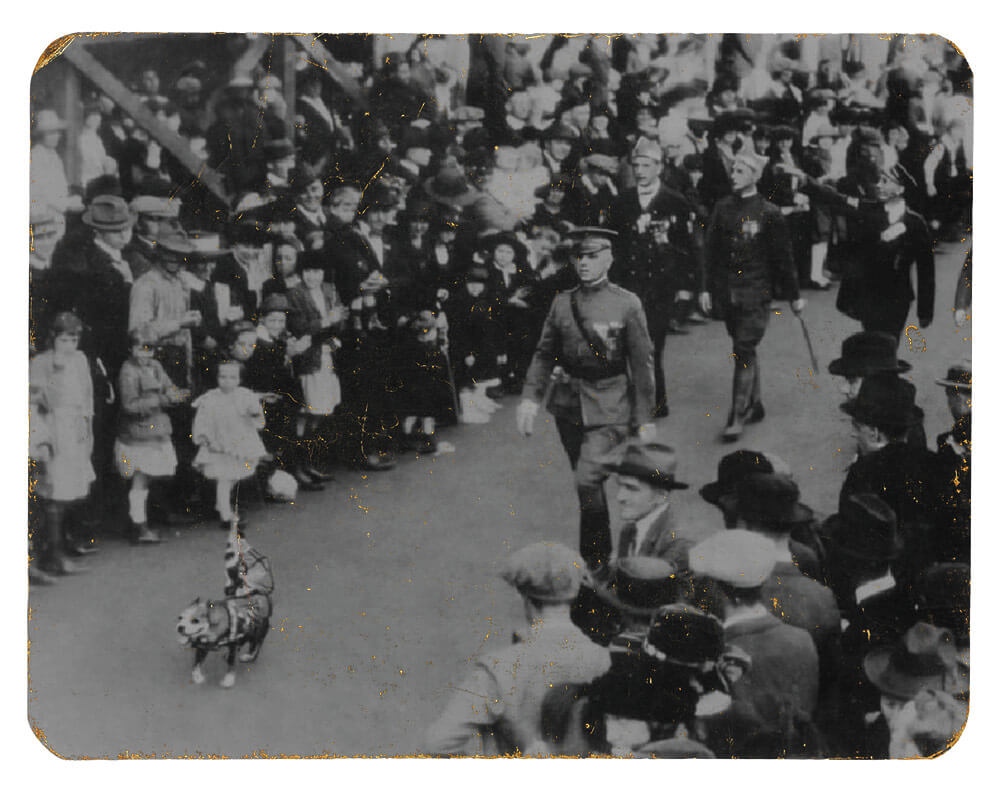

Stubby returned home a national celebrity. He marched in, and sometimes led, parades throughout the country. In time, he would meet three different presidents, and GEN John J. Pershing awarded Stubby a gold medal from the Humane Education Society in 1921.

In the fall of 1921, PVT Conroy started attending the Georgetown University Law Center, bringing Stubby with him. Stubby often acted as the Georgetown Hoyas’ mascot and performed at halftime of football games.

In 1926, Stubby died in his sleep. Following his death, Stubby’s skin was preserved and mounted on a plaster cast. Those remains and his blanket were put on display at the National Red Cross Museum.

In 1956, Stubby was donated to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., and he is still remembered today. In 2018, an animated film, Sgt. Stubby: An American Hero, was released that recounted his heroic story. The Connecticut National Guard calls Stubby “the most famous and decorated war dog in U.S. history.”

By Contributing Writer MAJ Darrin Haas