Preparing for “America’s Worst Day”

MG Michael Stone painted a grim picture to the assembled press at Camp Atterbury on April 13 of this year. The 31-year veteran of the Michigan Army National Guard and commander of the 46th Military Police (MP) Command, announced a 20-kiloton nuclear device had gone off in a West Coast suburb. Upwards of 20,000 people had been killed, 50,000 injured and 800,000 impacted. It was indeed what he called “America’s worst day.”

But in truth, it was all a drill. The mock press conference was part of Vibrant/Guardian Response, an annual (CBRN) response training exercise. Held April 4–18, this year’s event tested Soldiers’ ability to respond to a nuclear event in a major American city.

Vibrant Response 2018 – led by U.S. Army North and held at Camp Atterbury in Edinburgh, Indiana – was held in conjunction with U.S. Northern Command-sponsored Guardian Response, which was held simultaneously at the Muscatatuck Urban Training Center in Butlerville, Indiana. The exercises represented two sides of the same coin.

Vibrant Response evaluated command personnel – in this instance, the 46th MP Command – on their ability to organize and direct forces in the field from outside the simulated fallout zone. Guardian Response examined the ability of Soldiers entering ground zero to carry out the assignments originating from command.

The two exercises together represent one of the largest DoD confirmation exercises conducted for specialized response forces. Roughly 5,000 military personnel participated in the exercises, representing Army National Guard, active duty and Reserves.

Vibrant Response

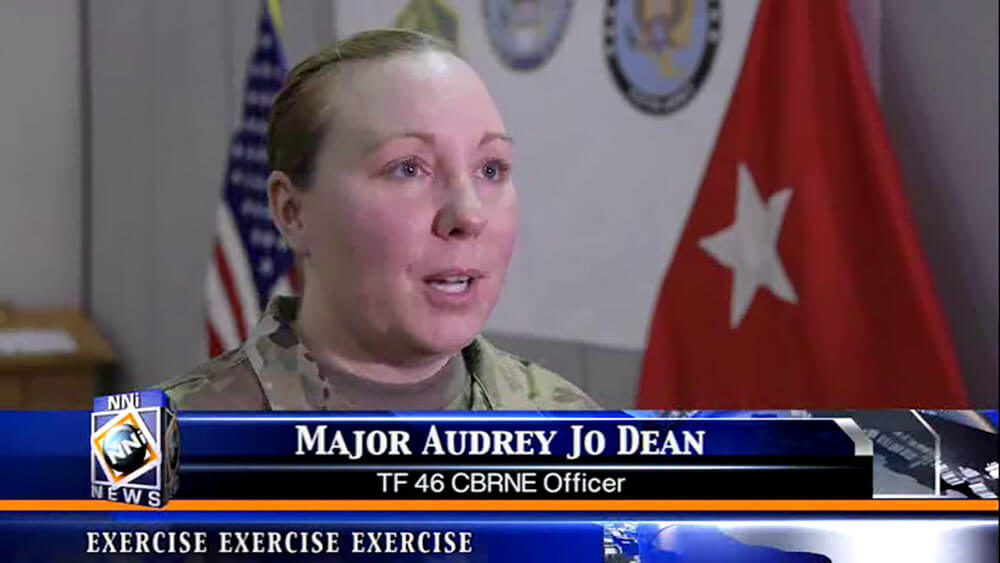

“Task Force 46 serves as the command and control of the Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Element Bravo, coordinating efforts in case of a catastrophic event in the United States,” said MG Stone. “Most of the members of the task force are [Guard] Soldiers, ready to help their neighbors recover and get back to a sense of normalcy as soon as possible.”

In the scenario, intelligence data point to a second device that might go off on the East Coast. “We have to – as a command – not only respond, but be looking and anticipating [whether] we are going to have to respond to a second device,” he added.

A bustling operations center, positioned in a building near the back of Camp Atterbury, was populated with tables, monitors, computers and Soldiers of the 46th busily attending to their roles in the exercise – conferring with each other or making their way in pursuit of a vital task. The Soldiers worked at tables grouped into separate areas that included intel, operations, logistics, IT, financial and contracts, public affairs, JAG and medical. Every area that would be needed in a real attack was represented in the scenario.

MSG Bill Beliew stood up from behind a computer at the CBRN table after collecting critical data to present to his superior.

“We’re training on how to give our commander the best information in the event there was a CBRN mission,” he explained. “He makes the best possible decision by populating the information on a map so he can see the affected areas. He makes decisions off of that.”

MSG Beliew commented on the overall effectiveness of the Vibrant Response exercise.

“It brings realism and an understanding of the importance of the mission in the event it ever had to actually be done,” he said.

LTC Tiffianey Laurin sat working at the logistics table. She juggled a mesmerizing number of moving parts to keep her assigned areas running smoothly. She commented on one area of responsibility in particular for an event of this magnitude – the logisticians’ role in partnering with agencies like Homeland Security and FEMA.

“We are really engaged with them [Homeland Security and FEMA]. We work to support them with commodities. We do a lot of logistical transport of things like food and infant supplies for civilians,” said LTC Laurin. We work with the civilian response centers so that they have food and water for displaced civilians during an incident. We do some patient transport and initial triage on the mass casualty decontamination lane [before patients] get transported to the local hospitals.”

She went on to note the importance of the logistician’s role in any mission. “If you do not have a good logistics plan, you’re not going to be able to operate. You cannot sustain your operations if you don’t have your logistics officer. They are critical.”

Along with logistics, communication is a critical link in any planned response.

SGT Brandon Garcia said he is one of a few Soldiers in the Michigan Guard licensed to operate what was the communications node of the exercise. Housed in a small unassuming van, the Emergency Response Vehicle (ERV) was parked outside the command center and plugged into the building.

“We can use the [ERV] anywhere we can get a satellite shot and connect internet and phones. It’s got 10 phones and enough data for about 20 people or so to work,” he said. “In Vibrant Response, we have the ERV on loan from Army North; it is our direct link to their network. We’re able to use it to do video conferencing and VOIP [Voice Over Internet Protocol] calls with them.”

In the wake of a real nuclear event, SGT Garcia would immediately report to his home station, prep a few vehicles, obtain situational awareness and travel to a point near the blast vicinity.

“The ERV is part of that initial push,” he explained. “We call it the torch. We would be some of the first Soldiers from the 46th MP Command on the ground.”

Reflecting on the takeaways of Vibrant Response, SGT Garcia noted, “What we get out of Vibrant Response is similar to what we get out of the different exercises building up to Vibrant Response – that’s to test ourselves. We want to find what we’re not doing well. We want to find the weak spots – the things that don’t work quite the way that we thought they would work. That way we can develop ways around that.”

Guardian Response

At a simulated ground zero at the Muscatatuck Urban Training Center, Soldiers worked to mitigate the mayhem caused by the mock detonation. The site was a hellish vision – scattered debris; burning vehicles; smoking and collapsed buildings; lifeless bodies, represented by mannequins lying in the streets; and plenty of walking wounded, played by local residents who had come out in support of the training.

Muscatatuck is one of DoD’s largest training facilities. Located on the campus of what was one of Indiana’s largest mental institutions, it includes paved roads, several large, fully constructed buildings and an integrated electromagnetic effects system that can cause malfunctions and performance degradation in the buildings.

“Muscatatuck is a fantastic training center,” said LTC Scotty Lene, U.S. Army North exercise chief for Vibrant Response. “You can flood houses to do rescue missions. It has real buildings that are demolished. The units actually go in and set up, then remove rubble piles. They clear roads. They set up decontamination lines. They are able to set up all the actual equipment to decontaminate, which in a real situation would hopefully prolong life and prevent people from being overexposed to radiation.”

Army National Guard units arrived on the scene at Muscatatuck ready with Mission Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP) suits, decon tents, radiation detectors, and search and extraction gear. Evaluators were scattered about, intently watching the exercise play out.

The scenario was life and death and the Soldiers were all business.

Maryland Army National Guard photo by SGT Devon Bistarkey

SSG John Smith with the 166th Engineering Company, Alabama Army National Guard, considered the mission ahead of him as he put on his MOPP suit. He said a good mission was one where everyone comes home safe. His squad was being evaluated on their urban search and rescue techniques.

“Today, I don’t know what we’re going to get thrown at us. It could include trench rescue, structural collapse, confined space or rope rescue,” he said. “That’s just the way the Army does it. You never know what you’re going to get into. You’ve got to be prepared for everything. We have [evaluators] out here and if there are any areas where we seem somewhat weak, we’ll find out from the instructors and actually become a better unit.”

SSG Ashley Taylor, a 12-year member of the 267th Engineer Detachment (Firefighters), South Carolina Army National Guard, was nearby, also prepping her MOPP suit. She was going out to perform search and rescue along with the squad from the 166th.

“All units come together and make this happen,” SSG Taylor commented. “It’s about mitigating the situation – getting downrange, rescuing, keeping ourselves safe, keeping everybody else safe. That’s the main thing to always learn from this mission.”

U.S. Army North

Back at Camp Atterbury, all activity – both at the command center with the 46th and at Muscatatuck – was being monitored by the exercises’ lead organization, U.S. Army North.

“We plan the entire exercise,” said LTC Lene. “We develop the scenario. We do all the order processing. Then we actually facilitate the exercise here from the exercise control. We’re tracking all missions. We’re tracking all of the injects – which are fictional events that we randomly add to the active scenario to stimulate Soldiers to react in real time.”

LTC Lene explained that it was Army North Soldiers who were performing the evaluations of the Guard Soldiers (in the coming weeks, roles would switch and Army National Guard leaders would be evaluating active duty Soldiers on the same tasks). The units’ ability to accurately respond to the real-time injects would weigh heavily in their overall evaluation scores.

Always Ready

In an actual nuclear event, the attack would last mere seconds, but recovery would go on for quite a long time. This is a reality that comes with its own set of challenges. During the press conference, MG Stone identified one such challenge. In the scenario, an estimated 6,000 hospital beds were available near the hypothetical blast zone, yet at least 50,000 people were injured. Figuring out how to deal with this type of seemingly impossible situation would be the ongoing job of the Army and partnering emergency response agencies.

National Guard Bureau photo by Luke Sohl

It’s not an easy situation to think about – not even for the Soldiers on the ground – but pushing fear and reservation aside in order to do what needs to be done is part of the job.

SPC Jason Justus had just reenlisted with the 118th Infantry Regiment, South Carolina Army National Guard, before he came to Atterbury to support the 46th in its Vibrant Response mission. His thoughts may be typical of many Soldiers.

“I hope a nuclear bomb doesn’t go off,” he said. “I actually try not to think about it too much. But these days you never know, so you’ve got to be prepared … especially with the threats we’re facing [today].”

This year’s Vibrant/Guardian Response exercises have indeed better prepared Guard Soldiers to respond to America’s worst day.

MG Stone announced that next year’s exercise might take place – in part – in the Detroit area. Guard leadership anticipates that holding the event in an actual urban city will increase its already high level of realism.

LTC Lene noted that in the wake of a real attack, the active duty component would need to rely on the steadfastness of the Army National Guard.

“Active duty Soldiers do the original footprint and then they’ll be replaced by the National Guard,” LTC Lene said. “They all do the enduring.”

By STAFF WRITER Matthew Liptak