At the time, the U.S. Army had 127,000 Soldiers and the Army National Guard had 181,000. But the U.S. needed millions of trained and equipped Soldiers to help the veteran forces of France and England.

Within 18 months, the Army would increase its force to 4 million (and 2 million were fighting in France when World War I ended on Nov. 11, 1918). The U.S. needed to supply its expanded force with arms, and the weapon most difficult to acquire and master in training was artillery.

The Army had nine authorized artillery regiments before the war. After the United States declared war, it formed 12 more regiments to supplement the National Guard and organized reserve artillery regiments, but that wasn’t enough. By the armistice, the United States had 234 artillery regiments.

Though the regiments were put in place, there weren’t enough experienced artillerymen, guns and ammunition to quickly train the needed force. One of the quickest and simplest solutions was to supply the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) with guns from France. There were plenty of qualified French artillery instructors and plenty of guns and ammunition being manufactured. Using those resources would simplify maintenance and supply in theater.

Back then, the United States had only a few 3-inch guns and 6-inch howitzers, and those were replaced primarily with French 75mm guns, and 155mm and 240mm howitzers.

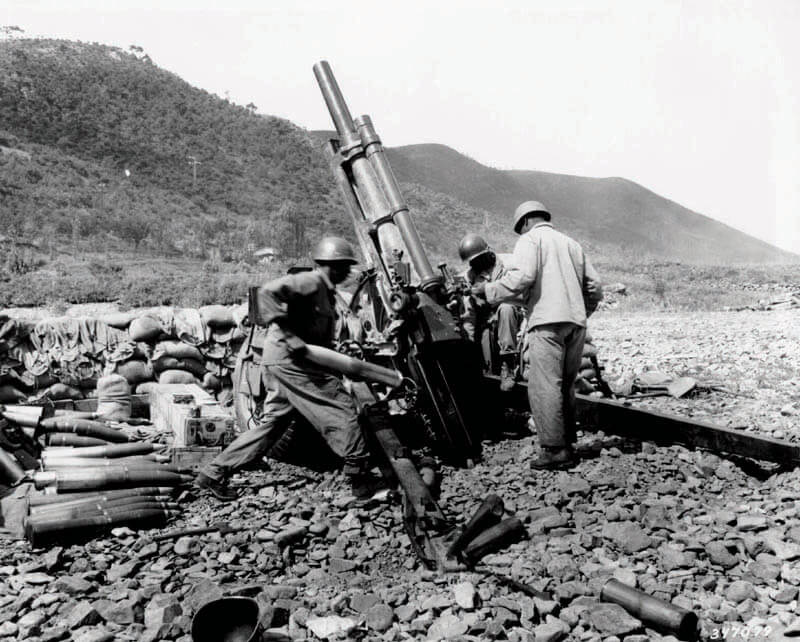

As it entered the war, the United States still believed that light artillery was the more suitable choice for warfare. When the U.S. Army organized its divisions for the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), each would have one artillery brigade with three artillery regiments – two light regiments with 48 75mm guns, and one heavy regiment of six batteries equipped with 24 French 155mm howitzers.

However, WWI’s trench warfare increased the need for heavy artillery pieces, such as the 155mm howitzer, and decreased the dependence on light field guns. Howitzers had a greater range and were more powerful, making them better suited for destroying fortified enemy targets and hitting rear areas.

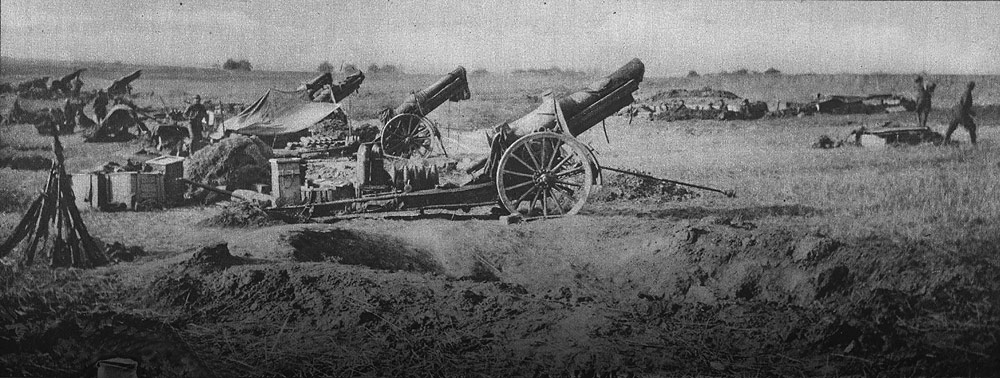

Because rapid artillery movement was not as critical, the Europeans fortified their artillery positions by building pits to protect them from counter-battery fire and camouflaged them to conceal their positions from aerial observers. That meant larger howitzers could be better supported and utilized.

The Advancement of the Howitzer

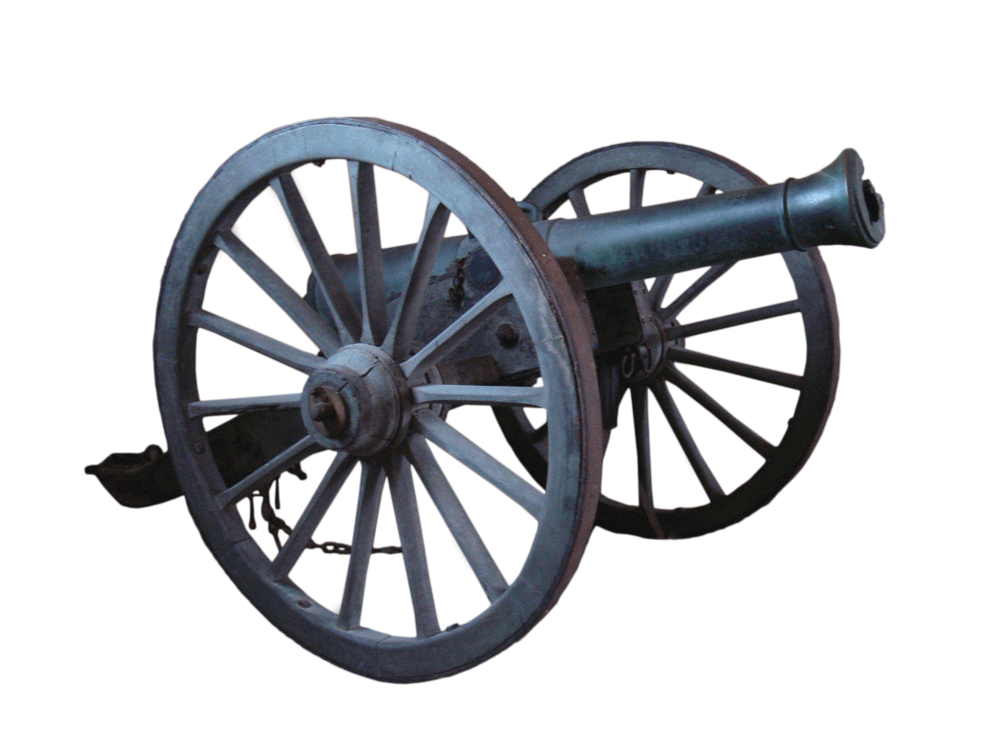

Licorne — 18th and 19th century muzzle-loading Howitzer produced in Luhansk, Russia.

12-pounder Napoleon — A “gun-Howitzer” of French design that saw extensive service in the American Civil War.

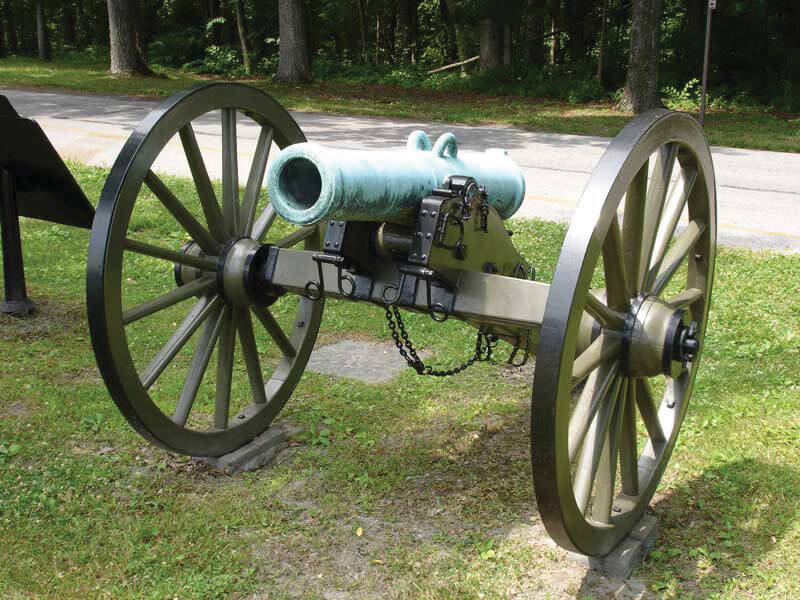

Mountain Howitzer — The longest serving artillery piece of the 19th century, the mountain Howitzer was in service from the time of the Mexican-American War to the Spanish-American War.

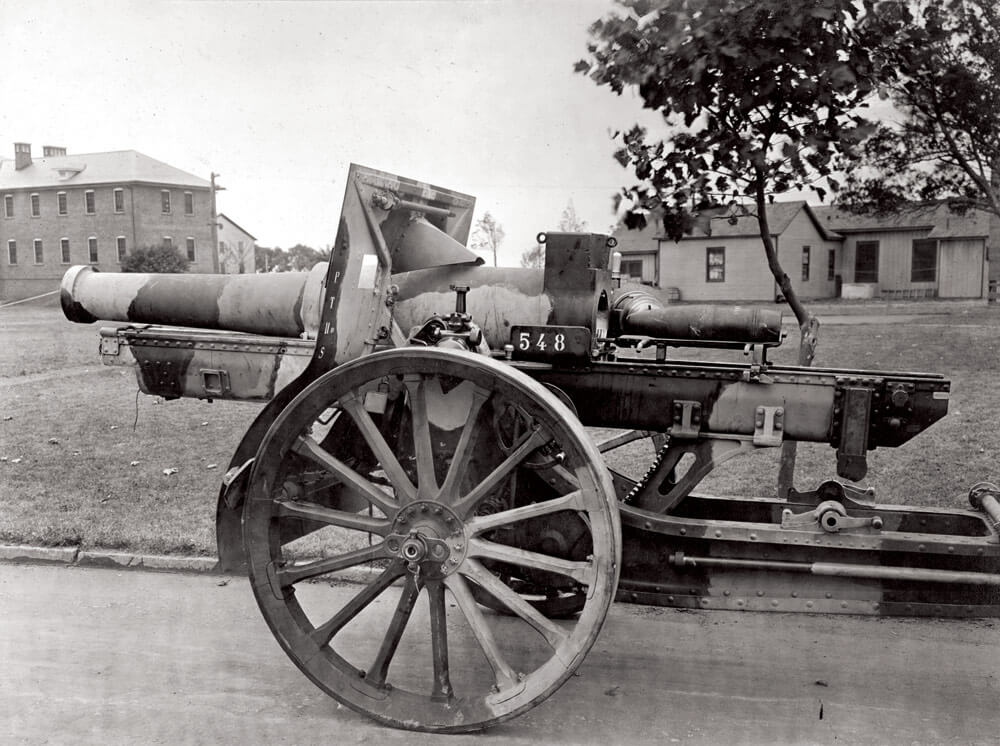

Schneider Howitzer — The standard Howitzer for the U.S. Army during WWI. The last American shot fired during the Great War was fired by a Schneider Howitzer called Calamity Jane, of the 11th Field Artillery Regiment.

M1A1 75mm Pack Howitzer — Developed between the two world wars, the M1A1 was the second most common Howitzer in WWII. It was transportable across difficult terrain and easily assembled and disassembled.

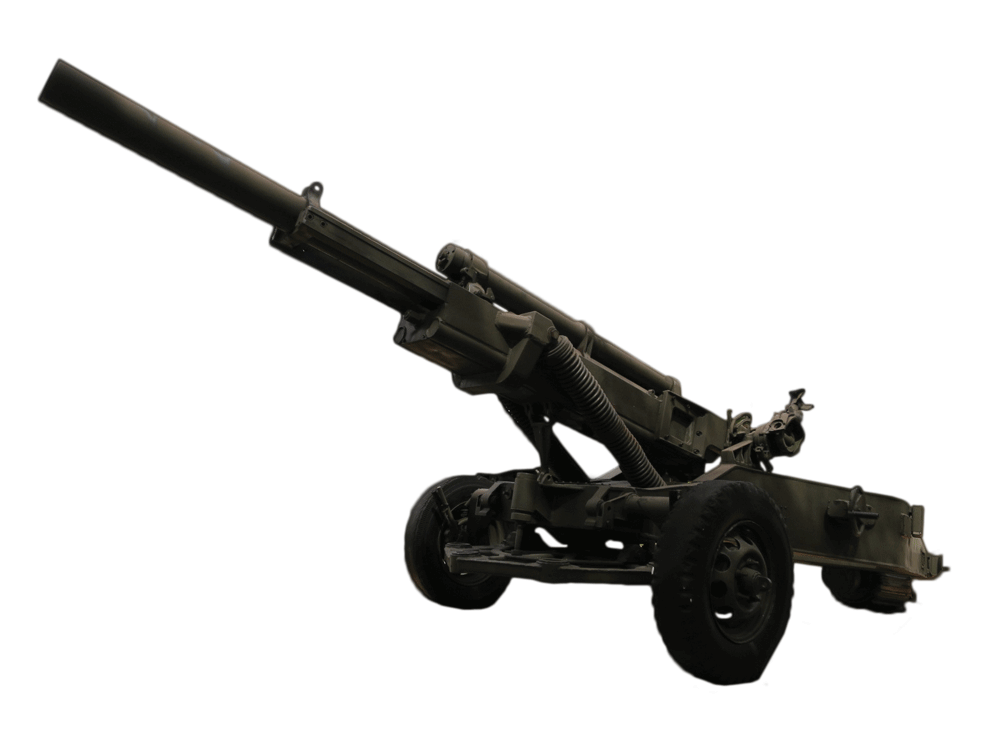

M101 105mm Howitzer — The standard U.S. light field Howitzer in WWII that saw action in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Entering production in 1941, it quickly gained a reputation for accuracy and carrying a powerful punch.

M102 105mm Howitzer — Replaced the Army’s M101 Howitzer during the Vietnam War, the new M102 was substantially lighter and could traverse a full 6,400 mils. With its low silhouette, the M102 was difficult for enemies to target.

M777A2 155mm Howitzer — Made in part from titanium, the M777A2 is 41 percent lighter than its predecessors. It uses a digital fire-control system, allowing it to be quickly put into action.

Howitzers have traditionally had a short barrel and used small charges to fire rounds at higher trajectories than traditional cannons. They’re capable of both high- and low-angle firing. Guns like the French 75mm generally fire rounds at a low angle while mortars fire rounds only at a high angle. This made howitzers more versatile and better suited for trench warfare.

The howitzer adopted by the U.S. Army for the war was the French Canon de 155 C modèle 1917 Schneider. The United States bought over 1,500 howitzers from the French to arm the AEF. The U.S. also began producing its own Model 1917, the 155mm Howitzer Carriage, based on the French design.

The M1917 weighed roughly 7,300 pounds with a barrel over seven feet long. The shells weighed around 100 pounds, and an experienced gunnery crew could fire three rounds per minute. Each projectile exited the barrel at a speed of 1,500 feet per second and had a maximum effective range of seven miles. The U.S. Army also built the M1918 155mm Howitzer, which was also modified from the French design.

When the 1st Tennessee Infantry Regiment was mobilized, it was reorganized as the 115th Field Artillery Regiment of the 55th Field Artillery Brigade in the 30th “Old Hickory” Division made up of Army National Guard Soldiers from North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee. The 115th was a heavy regiment that fired 155mm howitzers, but learning to fire these weapons was difficult. There were no French weapons in the States when the National Guard mobilized and the draft began. Newly formed artillery units, like the 115th, had to find creative ways to train without guns. They would use make-believe artillery and pretend horses, eventually building fake howitzers out of logs and branches for training.

They didn’t put their hands on actual howitzers until arriving at training camps in France.

Once the 115th received its howitzers, it became a lethal artillery regiment, firing rounds at the Battle of Saint-Mihiel and in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the largest and bloodiest battle in American history. Many other Army National Guard artillery units fought as well, helping bring World War I to a close and ushering in a more modern Guard force equipped with lethal weaponry.

By MAJ Darrin Haas

All Howitzer Photos Courtesy of the Library of Congress