PVT Henry Johnson was the first American war hero of the war to end all wars, but his fight did not end in the trenches.

According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, over 100,000 Americans died in World War I, a war which started just over a hundred years ago. Henry Johnson, then of the 369th Infantry Regiment, New York Army National Guard, popularly known as the “Harlem Hellfighters,” was not one of the many killed. However, he came very close to being added to the roll of the 16 million people worldwide that made the ultimate sacrifice during WWI.

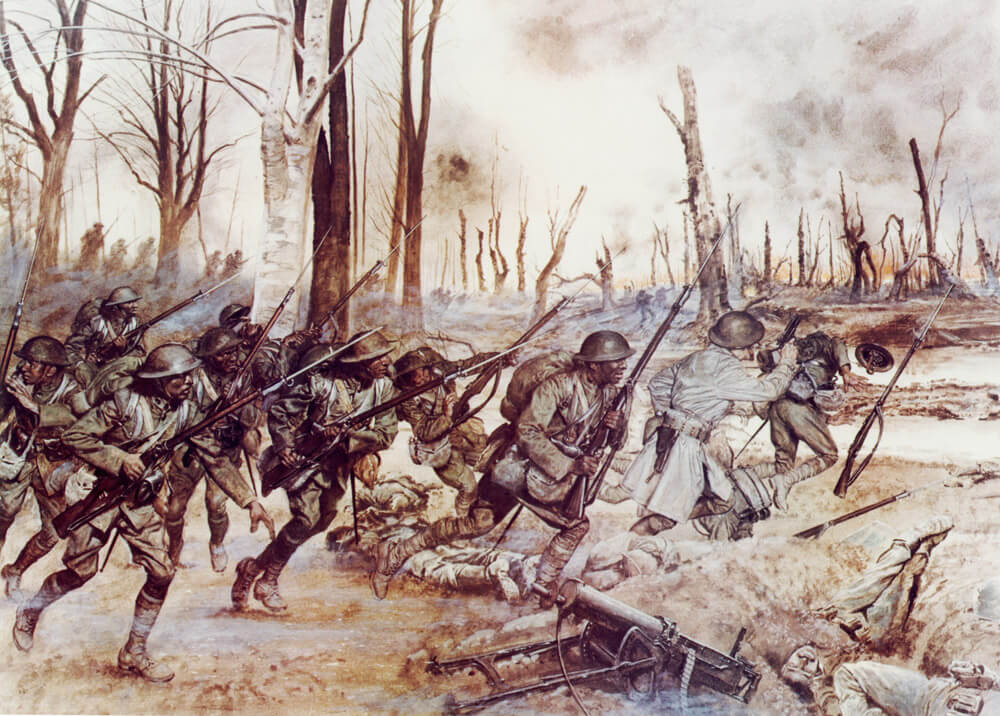

The 369th was the best known African American unit of WWI. Though the Soldiers of the unit desired to get into the fight in Europe, these men were often relegated to manual labor duties because White Soldiers refused to fight with them. In spite of this, requests for Soldiers from French Allies convinced GEN John J. Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front in World War I, to detach the 369th to the battlefield under control of the French Fourth Army’s 126th Division.

“They were organized in 1916 as a New York State National Guard Regiment,” said Courtney Burns, director of military history, New York State Military Museum. “They were anxious to prove that they were responsible citizens, that they were patriotic Americans and were willing to serve their part in [hopes of achieving] racial justice and equality.”

It was on the night of May 15, 1918, after having endured combat patrols, raids and artillery barrages, that PVT Johnson, 26 years old at that time, and PVT Needham Roberts, only 17 at the time, were dispatched to guard a bridge over the Aisne River in France. While the pair may have hoped for a mundane night of standing watch, the Germans had other ideas.

An enemy patrol with an estimated 20 to 24 troops had a mission to take out the outpost where the privates were stationed and bring them back as prisoners. When the clock turned towards 2:00 a.m., the German soldiers approached the position. Shots rang out and the sound of wire cutters put the two American privates on alert.

PVT Johnson opened a box of grenades and told PVT Roberts to run back and alert the main line of defense. At that moment, the first enemy grenades landed on their position. PVT Johnson threw grenades of his own, stalling the German patrol, but PVT Roberts was struck down with shrapnel wounds to his arm and hip.

Out of grenades, PVT Johnson took up his French rifle. According to Arthur Little, the commander of the 369th, who authored the 1936 book “From Harlem to the Rhine,” the French rifles issued to the 369th only had three rounds per clip.

“Johnson fired his three shots,” Little wrote. “The last one almost muzzle to breast of the Boche [German] bearing down upon him. As the German fell, a comrade jumped over his body, pistol in hand, to avenge his death. There was no time for reloading. Johnson swung his rifle round his head, and brought it down with a thrown blow upon the head of the German. The German went down.”

PVT Johnson looked over to assist PVT Roberts. He observed two Germans lifting the younger American Soldier up to carry him off towards the German lines.

“Our men were unanimous in the opinion that death was to be preferred to a German prison,” Little wrote. “But Johnson was of the opinion that victory was to be preferred to either.”

PVT Johnson ran to the aid of PVT Roberts. He whipped out his Army-issued bolo knife and went on the attack. Little continued:

“As Johnson sprang, he unsheathed his bolo knife, and as his knees landed upon the shoulders of that ill-fated Boche, the blade of the knife was buried to the hilt through the crown of the German’s head.”

The threat to PVT Roberts was eliminated and PVT Johnson turned to deal with the rest of the enemy. But he was struck by a bullet from an enemy automatic pistol. Even this did not stop the Doughboy. PVT Johnson lunged forward, stabbing and slashing at the enemy. His grim, relentless determination took the fighting spirit out of the enemy. The Germans panicked and retreated with the sounds of advancing Allied Soldiers drawing louder from the rear.

With the arrival of fellow Americans, at last, PVT Johnson’s and PVT Roberts’ struggle for survival was finished. PVT Johnson had sustained a total of 21 wounds in order to achieve his victory.

“Each slash meant something, believe me,” PVT Johnson told a reporter, according to a Smithsonian article on the historical events. “There wasn’t anything so fine about it. Just fought for my life. A rabbit would have done that.”

A 1920 New York Army National Guard report stated the German attackers had abandoned a considerable quantity of firearms, including automatic pistols at the scene. They had carried away their wounded and dead, but the report was able to draw some conclusions.

“He [PVT Johnson] killed one German with rifle fire, knocked one down with clubbed rifle, killed two with bolo, killed one with grenade, and, it is believed, wounded others,” the National Guard reported.

Both privates received France’s highest honor, the Croix du Guerre, after the battle. In 2015, PVT Johnson was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by President Barack Obama.

“Bottom line, they had a great impact on America as a whole, because it is an American story,” explained Krewasky A. Salter, Ph.D., a military history curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

Salter went on to note that PVT Johnson’s action may have briefly unified the country because he was the first American Soldier of any race to be recognized for conspicuous gallantry on the battlefield during WWI. But that unification did not last long. America’s racial troubles would continue to bear down on the Nation.

“I think the key [term] is ‘ever so briefly,’ because that was in May of 1918,” Salter said. “And then, of course, the war officially ends in November of 1918. Then, within six or seven months of the next year of 1919, we have this period that you may be aware of called the ‘Red Summer.’ ”

Because of his fame, the war hero went on the lecture circuit to speak on his WWI experiences in 1919. That truth included statements that were critical of the treatment of African-American Soldiers by their White counterparts before and during the war. PVT Johnson was forced out of his lecture work as a consequence.

Many other African-American Soldiers who were returning from WWI also spoke out against the inequality they experienced as returning Veterans. They had bled for freedom on the battlefields of Europe and now expected their freedoms back home in America.

The Red Summer was a result of this societal unrest. During the summer of 1919, race riots broke out across the country leading to many deaths. But the Civil Rights movement was decades off and, sadly, newly promoted SGT Johnson would not be there to see it. The Red Summer was just a foreshadowing of the long journey ahead for Black America.

Before the Red Summer, and after the 369th had returned home, there was a major parade for the Harlem Hellfighters in New York City in which SGT Johnson rode at the head.

The regiment was lauded not only for PVT Johnson’s fighting spirit, but for accomplishments of the unit as a whole. Soldiers from the 369th received 171 decorations of valor during the war and the entire unit was awarded the Croix du Guerre. It is said that not a single Harlem Hellfighter ever became a prisoner and that they never gave up a foot of ground during the war. The unit’s band is also credited with introducing Jazz to Europe.

PVT Johnson did what he could. He sacrificed almost everything for his country. He bled in the trenches of Europe for the United States. He spoke out against racism in the military when he was given the rare opportunity for an African-American voice to be heard publicly.

After having given almost everything, he was left with almost nothing. He went back to his hometown of Albany, New York, to try to get work. Sadly, he could no longer hold the railroad porter position he had before the war because his combat injuries prevented him from doing the heavy lifting required as part of that job. He died destitute in 1929, but was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full honors.

Today the 369th Sustainment Brigade and 369th Special Troops Battalion carries on the proud legacy of the Hellfighters as an Army National Guard unit out of Harlem, New York.

By Staff Writer Matthew Liptak